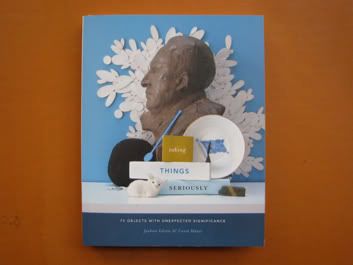

Judith Pascoe wrote a fascinating little book called T

he Hummingbird Cabinet - A Rare and Curious History of Romantic Collectors. The section detailing the passionate collecting of hummingbirds in the early 1800s emphasizes how much the nature of display provides insight into the intentions and sentiments which drive the pursuit of a collection. In the context of the London Natural History museum, Pascoe details a contrast in the museum's modern purposes and those of the hummingbird display:

The hummingbird cabinet that survives in the Natural History Museum is positioned in close proximity to a beak exhibit featuring the severed heads of puffin, butcher bird, and hornbill. The signage in the gallery is defensive in tone. Posted next to the hummingbird cabinet is a small cardboard placard headed with the phrase "An Antique Collection"... The Natural History Museum wants visitors to know that the specimens in this gallery are from the museum's historical bird collection, "which dates back over the last two hundred years." A card attached to a floor-to-ceiling case concedes that "the Museum no longer has an active collecting programme and would only display new speciments within rigorous conservation guidelines". The gallery's curators anticipate the opening of "a new, permanent bird gallery, presenting a contemporary view of bird biology, ecology and conservation using some of the latest techniques in multi-media display."

The new gallery will be unlikely to shed any light on the longings and desires that were evoked by hummingbirds in the romantic period. It will not, I expect, help us to see how romantic modes of feeling fueled the pursuit of hummingbirds, or how they influenced the style of their display, or why they drove some admirers of the birds to a state of desolate despair. To understand those things, you are better off studying the antique hummingbird cabinet even though it uses one medium, presents an innacurate view of bird biology, and has nothing to say about ecology and convervation.

The hummingbird cabinet is large but easy to overlook; from a distance it looks like a neglected terrarium in which the foliage has been allowed to dry. But if you peer closely at this desiccated thicket, it blooms with hundreds of hummingbirds posed stiffly on every branch.

Two different displays, and two very different ideas about why these items were worth displaying. As we “read the arrangement” of a collection, the message it communicates becomes quite defined.